Drug-induced Parkinsonism: Causes, Symptoms, Treatment, Drug List

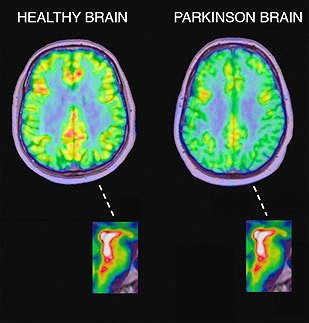

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive nervous system disorder that affects movement. Symptoms start gradually, sometimes starting with a barely noticeable tremor in just one hand. Tremors are common, but the disorder also commonly causes stiffness or slowing of movement.

In the early stages of Parkinson’s disease, your face may show little or no expression. Your arms may not swing when you walk. Your speech may become soft or slurred. Parkinson’s disease symptoms worsen as your condition progresses over time.

Although Parkinson’s disease can’t be cured, medications might significantly improve your symptoms. Occasionally, your doctor may suggest surgery to regulate certain regions of your brain and improve your symptoms.

Symptoms

Parkinson’s disease signs and symptoms can be different for everyone. Early signs may be mild and go unnoticed. Symptoms often begin on one side of your body and usually remain worse on that side, even after symptoms begin to affect both sides.

Parkinson’s signs and symptoms may include:

- Tremor. A tremor, or shaking, usually begins in a limb, often your hand or fingers. You may rub your thumb and forefinger back and forth, known as a pill-rolling tremor. Your hand may tremble when it’s at rest.

- Slowed movement (bradykinesia). Over time, Parkinson’s disease may slow your movement, making simple tasks difficult and time-consuming. Your steps may become shorter when you walk. It may be difficult to get out of a chair. You may drag your feet as you try to walk.

- Rigid muscles. Muscle stiffness may occur in any part of your body. The stiff muscles can be painful and limit your range of motion.

- Impaired posture and balance. Your posture may become stooped, or you may have balance problems as a result of Parkinson’s disease.

- Loss of automatic movements. You may have a decreased ability to perform unconscious movements, including blinking, smiling or swinging your arms when you walk.

- Speech changes. You may speak softly, quickly, slur or hesitate before talking. Your speech may be more of a monotone rather than have the usual inflections.

- Writing changes. It may become hard to write, and your writing may appear small.

What is drug-induced parkinsonism?

About 7% of people with parkinsonism have developed their symptoms following treatment with particular medications. This form of parkinsonism is called ‘drug-induced parkinsonism’. People with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease and other causes of parkinsonism may also develop worsening symptoms if treated with such medication inadvertently.

What is the connection between Parkinson’s disease and drug-induced parkinsonism?

Any drug that blocks the action of dopamine (referred to as a dopamine antagonist) is likely to cause parkinsonism. Drugs used to treat schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders such as behavior disturbances in people with dementia (known as neuroleptic drugs) are possibly the major cause of drug-induced parkinsonism worldwide.

Parkinsonism can occur from the use of any of the various classes of neuroleptics. The atypical neuroleptics – clozapine (Clozaril) and quetiapine (Seroquel), and to a lesser extent olanzapine (Zyprexa) and risperidone (Risperdal) – appear to have a lower incidence of extrapyramidal side effects, including parkinsonism. These drugs are generally best avoided by people with Parkinson’s, although some may be used by specialists to treat symptoms such as hallucinations occurring with Parkinson’s. Risperidone and olanzapine should be used with caution to treat dementia in people at risk of stroke (the risk increases with age, hypertension, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, smoking and high cholesterol), because of an increased risk of stroke and other cerebrovascular problems. It is unclear whether there is an increased risk of stroke with quetiapine and clozapine.

While these drugs are used primarily as antipsychotic agents, it is important to note that they can be used for other non-psychiatric uses, such as control of nausea and vomiting. For people with Parkinson’s, other anti-sickness drugs such as domperidone (Motilium) or ondansetron (Zofran) would be preferable. As well as neuroleptics, some other drugs can cause drug-induced parkinsonism. These include some older drugs used to treat high blood pressure such as methyldopa (Aldomet); medications for dizziness and nausea such as prochlorperazine (Stemetil); and metoclopromide (Maxolon), which is used to stop sickness and in the treatment of indigestion.

Calcium channel blocking drugs used to treat high blood pressure, abnormal heart rhythm, angina pectoris, panic attacks, manic depression and migraine may occasionally cause drug-induced parkinsonism. The most well-documented are cinnarizine (Stugeron) and flunarizine (Sibelium). Calcium channel blocking drugs are, however, widely used to treat angina and high blood pressure, and it is important to note that most common agents in clinical use probably do not have this side effect. These drugs should never be stopped abruptly without discussing with your doctor.

A number of other agents have been reported to cause drug-induced parkinsonism, but clear proof of cause and effect is often lacking. Amiodarone, used to treat heart problems, causes tremor and some people have been reported to develop Parkinson’s-like symptoms. Sodium valproate, used to treat epilepsy, and lithium, used in depression, both commonly cause tremor which may be mistaken for Parkinson’s. Some reports have linked SSRI antidepressant drugs such as fluoxetine (Prozac) to drug-induced parkinsonism but hard evidence of cause and effect is unsubstantiated. This type of drug is increasingly used to treat depression in Parkinson’s.

What are the characteristics of drug-induced parkinsonism and how does it differ from idiopathic Parkinson’s?

Drug-induced parkinsonism is more likely to be symmetrical (on both sides of the body) and less likely to be associated with tremor, although it can sometimes present asymmetrically and with a tremor. Akinesia with loss of arm swing can be the earliest feature. Bradykinesia can be an early common symptom, causing expressionless face, slow initiation of movement and speech difficulties.

Other drug-induced movement disorders

Tardive dyskinesia is another drug-induced movement disorder that can occur in people who are on neuroleptic drugs. This refers to excessive movement of the lips, tongue and jaw (known as oro-facial dyskinesias). The term ‘tardive’ means delayed or late appearing and this refers to the fact that the person may have been treated with the neuroleptic for some time before the dyskinesia becomes apparent. Tardive dyskinesia can be difficult to treat and may sadly be permanent in some people.

Are there any other risk factors for drug-induced parkinsonism?

The incidence of drug-induced parkinsonism increases with age. Drug-induced parkinsonism is more prevalent in older people and is twice as common in women than men. Other risk factors include a family history of Parkinson’s and affective disorders. There may be a genetic predisposition to drug-induced parkinsonism. Younger people may develop sudden onset of dystonia (abnormal muscle postures) and abnormalities of eye movements if treated with drugs that cause drug-induced parkinsonism.

How quickly will the symptoms of drug-induced parkinsonism appear after someone starts taking a drug that may cause it?

It depends on the properties of the drug. In 50% of cases, the symptoms generally occur within one month of starting neuroleptics. In some older people, features can be identified as early as the fourth day of treatment, and sometimes after one dose. However, there can occasionally be a delayed development of parkinsonism.

How does drug-induced parkinsonism progress?

Drug-induced parkinsonism tends to remain static and does not progress like idiopathic Parkinson’s but this is not usually all that helpful in making the diagnosis.

If the offending drug is stopped, will the drug-induced parkinsonism improve and if so, how long will this take?

Generally, 60% of people will recover within two months, and often within hours or days, of stopping the offending drug. However, some people may take as long as two years. One study reported that 16% of cases went on to be confirmed to have idiopathic Parkinson’s. These people were probably going to develop Parkinson’s at some stage in the future in any event, but the offending drug ‘unmasked’ an underlying dopamine deficiency. This theory is supported by research studies with specialist PET scans.

What other treatment is available?

In many cases, the first approach to treatment will be to try stopping the offending drug for a sufficient length of time, reducing it, or changing it to another drug that may be less likely to cause drug-induced parkinsonism. Please note: you should not stop taking any drug because you think it is causing drug-induced parkinsonism, or worsening existing Parkinson’s without first discussing the situation with your doctor.

Some drugs need to be withdrawn slowly, particularly if the person has been taking the drug for a considerable time, and problems can arise if they are withdrawn abruptly. Sometimes, for medical reasons, the person cannot stop taking the drug that causes drug-induced parkinsonism. Where this is the case, the benefits of the drug need to be weighed against the side effects of parkinsonism.

Sometimes, adjusting the dose of the neuroleptic drug downwards to a level that does not cause parkinsonism may help. However, this is not always possible, without taking the dose to a sub-therapeutic level (i.e. a level where it is not as effective at treating the psychotic illness for which it is prescribed). Usually, changing the medication to an atypical neuroleptic is the best approach. If it is not possible to stop taking the offending drug, then anticholinergic drugs may be used. However, these are best avoided in older people, because they may cause confusion, as well as worsening tardive dyskinesia. Amantadine (Symmetrel), another drug used to treat Parkinson’s, can also be used to treat drug-induced parkinsonism if the person cannot stop taking the offending drug.

However, like anticholinergic drugs, amantadine may also cause confusion, and sometimes psychosis in older people, and therefore is more suitable for younger people with drug-induced parkinsonism.

Can these drugs aggravate existing idiopathic Parkinson’s disease?

Yes. Stopping the medication (where possible) may be enough to relieve the drug-induced parkinsonism, although improvements can take several months.

Can illegal drugs such as heroin cause drug-induced parkinsonism?

In the late 1970s, a group of drug users in California took synthetic drugs, manufactured illegally, as a cheap alternative to heroin. One of these addicts, aged 23 years, became ill and over several days developed symptoms of parkinsonism, such as tremor, rigidity and akinesia. When he was treated with anti-Parkinson’s drugs, he improved dramatically.

When he died from an overdose of other drugs, a postmortem examination was carried out and it was found that severe damage had been done to the dopamine containing cells in the basal ganglia, similar to that seen in Parkinson’s. He was uncharacteristically young to have developed Parkinson’s, so doctors suspected that the illegal drugs he was taking had caused his condition. They analysed the material that he had used in the manufacture of the drugs and they found it contained a chemical called MPTP.

Further research showed that a breakdown product of MPTP was capable of producing severe damage to the dopamine-containing cells in the basal ganglia. Since this first case, other drug addicts have developed a similar syndrome after injecting themselves with drugs contaminated by MPTP. Although rigorous research into other illegal drugs is limited to date, theoretically, cocaine, ecstasy and other illegal drugs may also be possible causes of drug-induced parkinsonism. More research in this area is needed.

I have read that some illegal drugs may actually improve the symptoms of Parkinson’s. Is this true? A BBC TV Horizon program, broadcast in the UK in February 2001, featured a person with Parkinson’s who found that some of his Parkinson’s symptoms were improved temporarily when he took ecstasy. Ecstasy is known to affect a neurotransmitter called serotonin. The levels of serotonin are abnormal in brains of people with Parkinson’s and the findings of the BBC Horizon program have suggested that further research into the relationship between serotonin and Parkinson’s is needed and may lead to the development of new non-dopaminergic treatments for the condition in the future.

Media attention in recent years has also focused on the role that cannabis may play in the management of pain in neurological conditions like multiple sclerosis. This is now being researched. At present, there is little information available on research into cannabis and Parkinson’s.

Neuroleptic drugs – drugs used to treat schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders.

Neurotransmitters – chemical messengers produced by the nerve cells in the brain. Their purpose is to pass messages from the brain to other parts of the body.

List of neuroleptic drugs

List of neuroleptic drugs available are:

- Amisulpride (Solian)

- Chlorpromazine hydrocloride (Chloractil/Largactil)

- Clozapine (Clozaril, Denzapine)

- Flupenthixol (Depixol)

- Fluphenazine hydrochloride (Modecate/Moditen/Motival (includes nortriptyline)

- Haloperidol Dozic/Haldol/Serenace)

- Methotrimeprazine/Levomepromazine (Nozinan)

- Olanzapine (Zyprexa)

- Oxypertine (Oxypertine)

- Pericyazine (Neulactil)

- Perphenazine (Fentazin, Triptafen (Perphenazine+amitriptyline)

- Pimozide (Orap)

- Pipotiazine (Piportil)

- Prochlorperazine (Stemetil)

- Promazine hydrochloride (Promazine)

- Quetiapine (Seroquel)

- Risperidone (Risperdal)

- Sulpiride (Domatil/Sulpitil/Sulpor (Sulparex is discontinued)

- Thioridazine (Melleril)

- Trifluoperazine (Stelazine)

- Zuclopenthixol acetate (Clopixol)

- Zotepine (Zoleptil)

Other drugs that can cause drug-induced parkinsonism

- Amiodarone (Cordarone X)

- Cinnarizine (Stugeron)

- Fluphenazine (Motival, Motipress)

- Lithium (Camcolit, Li-Liquid)

- Methyldopa (Aldomet)

- Metoclopramide (Maxolon)

- Tranylcypromine (Parnate)