Link Between Vitamin D Deficiency and Obesity Unclear

By Carla Nieto Martínez

The role of vitamin D in the risk for overweight and obesity has been the subject of multiple studies. Though there’s still not enough evidence to reach a decisive conclusion, several ongoing debates are setting the stage for future research.

Irene Bretón, MD, PhD, discussed these debates in a presentation titled “Vitamin D Deficiency and Obesity: Cause or Consequence?,” delivered at the 64th Congress of the Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition (SEEN). Bretón is president of the Foundation of the Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition.

“Vitamin D deficiency can arise from different causes. The percentage that can be attributed to solar radiation is extremely variable. Some studies put it at 80%, while others suggest lower figures. Many diseases have also been associated with vitamin D deficiency or with low vitamin D levels (which are not always at the level of deficiency). Nonetheless, we still have a lot to learn about these associations,” she said.

Bretón pointed out that many of these studies overlook parathyroid hormone testing. “I also think it’s more appropriate to discuss nutritional status of vitamin D as opposed to serum levels, because these data can be misleading. It would be interesting to focus more on vitamin D metabolism and not just plasma levels.”

Vitamin Deficiency

To answer whether obesity and its complications could be related to low vitamin D levels, Bretón pointed to this vitamin’s profile in various regions of the world and called attention to the fact that none of the studies on this topic include populations with roughly adequate levels of this vitamin.

“This highlights the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency worldwide. It affects approximately 50% of the population, has been described in all age groups, and affects both men and women — particularly pregnant women and those in menopause — and older adults,” said Bretón.

She also cited the figures backing this fact: 88% have 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels < 30 ng/mL, 37% have levels < 20 ng/mL, and 7% have levels < 10 ng/mL.

“These percentages have brought us to consider their potential link to the current obesity epidemic. Studies in humans have observed a relationship between low plasma levels and markers for obesity and adiposity. Free 25-hydroxyvitamin D and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D are known to be reduced in obesity, and treatments to correct vitamin D deficiency are less effective in people with the disease,” she noted.

Regarding the impact in “the opposite direction,” that is, whether obesity affects the nutritional status of vitamin D, Bretón explained that observational studies have generally found a relationship between overweight and obesity and lower plasma levels of vitamin D. “Data from these studies show that each kg/m2 increase in [body mass index (BMI)] is associated with a 1.15% decrease in 25-hydroxyvitamin D. These studies also show that the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency is 35% higher in patients with obesity and 24% higher in those that are overweight compared with individuals of normal weight. A relationship has been observed between vitamin D deficiency and body fat percentage in men and women and in all age groups,” explained Bretón.

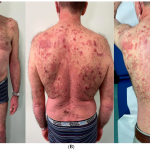

Bretón noted that the diseases most closely associated with obesity are type 2 diabetes, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, cancer (colon, breast, prostate, and ovarian), inflammatory liver disease, asthma, and inflammatory diseases.

Mechanisms Involved

Bretón reviewed the latest evidence on the mechanisms involved in the relationship between obesity and vitamin D deficiency. “People with obesity may experience less solar exposure (more of their body is covered, or they spend more time indoors), but reduced exposure to the sun is known to have less of an influence on vitamin D levels. Studies where people were given radiation to test how their plasma levels of vitamin D respond have found that there is a smaller effect in people with obesity, and that the effect is inversely correlated with BMI: the higher the BMI, the less vitamin D levels increase under exposure to solar radiation.”

Another mechanism is sequestration in adipose tissue, which is the largest reservoir of vitamin D in the body. Nevertheless, factors such as vitamin D concentration in this tissue, regulation of local metabolism, and vitamin uptake and release are less understood. It is therefore unclear whether this mechanism acts to regulate plasma levels.

“This is why severe vitamin D deficiencies (and deficiencies of other fat-soluble vitamins) that occur after bariatric surgery are often not seen in the first year after surgery but develop much later, when the vitamin that has accumulated in adipose tissue is released as weight is lost,” said Bretón.

“On the other hand, the volumetric dilution in blood that occurs in relation to total body fat content may explain the variability of plasma levels and the response to treatment. Predictive equations have been described,” she explained.

The Prenatal Stage

Bretón mentioned that the best setting for studying the impact of vitamin D and preventing future obesity is during the initial stages of life, when adipogenesis and fetal programming are occurring.

“Studies in animals have shown how maternal vitamin D deficiency (due to nongenetic or nonepigenetic mechanisms) leads to changes in adipogenesis and programming of adipose reserves. A fetal or perinatal environment with low vitamin D levels programs all these mechanisms differently, and not just adipogenesis and adipocyte differentiation in utero,” she added.

Various mechanisms involved in vitamin D deficiency as a cause of obesity are currently being studied in the prenatal setting. One such mechanism is the interaction between the vitamin D receptor and 1 alpha–hydroxylase, which are present in the adipose tissue and help modulate lipid metabolism.

“The vitamin D receptor is particularly expressed in the early stages of adipocyte differentiation, but its expression drops off as the differentiation process continues. Vitamin D receptor knockout mice have a slender phenotype and are resistant to diet-induced obesity. They also accumulate less fat with age and a high-fat diet,” explained Bretón.

“However, vitamin D also influences the production of inflammatory adipokines in these early stages of life. It specifically plays a central role in modulating the inflammatory response in adipose tissue. These anti-inflammatory effects appear to be mediated by inhibition of [NF–kappa B] and MAPK signaling pathways. All of this suggests that vitamin D influences both adipogenesis and how the adipose tissue functions,” she added.

Weight Loss

When considering the link between vitamin D and obesity in the context of weight loss, Bretón explained that studies in this area suggest that weight loss per se is not sufficient to increase serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D. Rather, increased synthesis by the skin or increased dietary intake are the most relevant factors for the nutritional status of this vitamin.

“A recent systematic review looking at the relationship between vitamin D levels and weight loss via caloric restriction and exercise showed a small but significant effect in the sense that weight loss increases vitamin D levels. However, other meta-analyses have not found significant results in this area,” she said.

“In my opinion, these results depend on how long the intervention is performed. If a lot of weight is lost in a short time frame, vitamin D is released into the adipose tissue, a process that doesn’t have any significant impact on the nutritional status of this vitamin. Generally, the effect of this relationship is small (1.5 ng/mL) and of little clinical relevance. Moreover, many systematic reviews have analyzed this relationship following bariatric surgery and have also come up with inconclusive results,” Bretón added.

What role do treatments play in correcting vitamin D deficiency? Bretón explained that studies that have examined how fortified foods affect obesity show that though these foods don’t cause significant weight changes, they do affect fat mass and waist circumference. This finding suggests that fortified foods have some impact, not necessarily on weight but perhaps on adiposity.

“To rightly value all this data, one has to pay special attention to the environment and the context where the research took place (children or adults, baseline vitamin D levels, and so on). If fortified foods are directly supplemented with cholecalciferol, the results are very inconsistent. We therefore cannot say that treatment with vitamin D can reduce body weight and adiposity,” she said.

When it comes to the complications from obesity, studies of vitamin D supplementation, cancer, and cardiovascular disease did not find any beneficial effect on preventing these pathologies.

For obesity’s impact on vitamin D supplementation, it is known that the levels achieved are lower in patients with obesity compared with patients of normal weight. “Compared with other interventions, however, these levels (15.27 ng/mL) are clinically relevant,” she noted.

Future Directions

Bretón explained that all this evidence has revealed many debates regarding the association of vitamin D levels with obesity. “For example, it appears that obesity could predict low vitamin D levels (not necessarily a deficiency). In turn, these low levels could cause obesity, especially during embryonic development, when programming of adipocyte physiology is taking place.”

Bretón sees many confounding factors that will need to be elucidated in the future. “One factor is that we aren’t sure whether the patient we’re seeing has vitamin D deficiency or if other factors are in play, like time since weight loss, laboratory technique used to measure vitamin D, nutritional status, geographic location, time of year when the test is performed, et cetera. You also have to assess other factors having to do with obesity, like how adiposity is being measured and whether BMI reflects that adiposity.”

Last, the expert reviewed the major research efforts underway that are based on evidence that vitamin D is associated with insulin resistance. Studies are being performed on pancreatic function, the role of vitamin D levels in ovarian physiology related to insulin resistance (specifically, the role of hyperandrogenism), adipose tissue (vitamin D receptor expression, volumetric dilution), and other components of metabolic syndrome to determine how this vitamin’s status influences the renin-angiotensin system, apoptosis, and cardiovascular risk.

“There is also plenty of research going on surrounding metabolic liver disease, which has a lot to do with the microbiota. So, they’re studying the relationship between vitamin D and dysbiosis, especially regarding local immunomodulation in the gut in relation to the microbiota,” she added.

Another area of research is cancer, focusing primarily on analyzing the nutritional status of vitamin D in relation to the microbiome and how this status may affect the therapeutic effect of chemotherapy and radiation therapy. “It would be interesting to find out whether the effect of immunotherapy varies depending on the patient’s vitamin D status,” concluded Bretón.

Bretón’s lecture at the 64th Congress of the SEEN was sponsored by the Foundation for Analysis and Social Studies (FAES).

This article was translated from the Medscape Spanish edition.