Cancer Drugs: Push For US-China Collaboration Begins

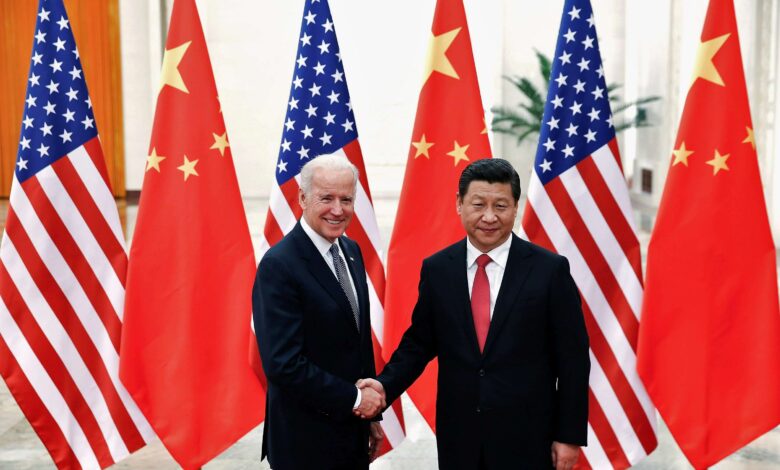

According to a report by the Financial Times, global drug-makers, regulatory officials and scientists are teaming up to push the US and China to co-operate on research to speed up the process of developing new cancer drugs through a form of “ping-pong diplomacy”.

The Bloomberg International Cancer Coalition will be launched in Singapore later this month to create a body through which the two countries can collaborate, despite recriminations and division between the superpowers during the pandemic.

By tapping the two largest populations of cancer patients in the world, the coalition aims to significantly reduce the time needed to collect enough data to prove a new drug is safe and effective. Concrete goals include creating standards on how patients are selected for the new, more tailored, cancer medicines.

The coalition includes representatives of western pharmaceutical companies such as Johnson & Johnson and Amgen, and Chinese drugmakers including Jiangsu Hengrui Medicine, BeiGene, Innovent Biologics and Zai Lab, as well as leading academics in the US and China. But it does not yet include any Chinese officials or the regulator.

Kevin Rudd, former prime minister of Australia, who is helping to steer the effort in his role as head of the Asia Society, compared it to the attempt in the 1970s to thaw relations between the US and China using table tennis.

“The US-China relationship has got so bad that we at the Asia Society have formed a view that cancer treatment trials may well become the next iteration of ping-pong diplomacy, to get this relationship back on the rails,” he said.

Rudd added the coalition would need to overcome concerns about intellectual property, particularly the protection of genetic codes.

The coalition will have to cope with the fallout from the pandemic, which began in Wuhan, China. A US intelligence agency recently said it was plausible that the virus escaped from a Wuhan lab by accident. China has not co-operated in the investigation and the US intelligence community has not reached a definitive conclusion. Four other agencies disagreed and a further three were unable to reach any kind of conclusion.

“Covid should have represented the classic case study of a global public good, which should have triumphed over the normal politics and geopolitics of a fraught political relationship,” Rudd said. “In fact, it did the reverse: it compounded a pre-existing difficulty between Beijing and Washington rather than provide the places to engage in serious combined collaborative research programmes.”

The coalition plans to use the US Food and Drug Administration’s Project Orbis, where the regulator works with peers in countries including Canada, Australia and Switzerland, as a model to make it easier to conduct clinical trials that cross borders and simplify regulatory submissions.

Lumykras, a drug produced by US biotechnology company Amgen, was approved in the UK using Project Orbis. Bob Li, an oncologist at US cancer research centre Memorial Sloan Kettering, said he hoped to replicate the successful global trial for Lumykras that helped cut the approval time for the innovative cancer treatment targeting the hard-to-treat KRAS mutation from 15 years to just three.

He also said rapid patient recruitment in China had helped AstraZeneca’s lung cancer drug Tagrisso, which targets a mutation more often found in the tumours of Asian women, to be developed in record time.

“Because of the scale of the cancer patient population in China we have the ability to execute things very fast.”